The geometric modification of an at-grade intersection can be achieved, where necessary, by realignment and/or channelization.

E 557.1 Realignment

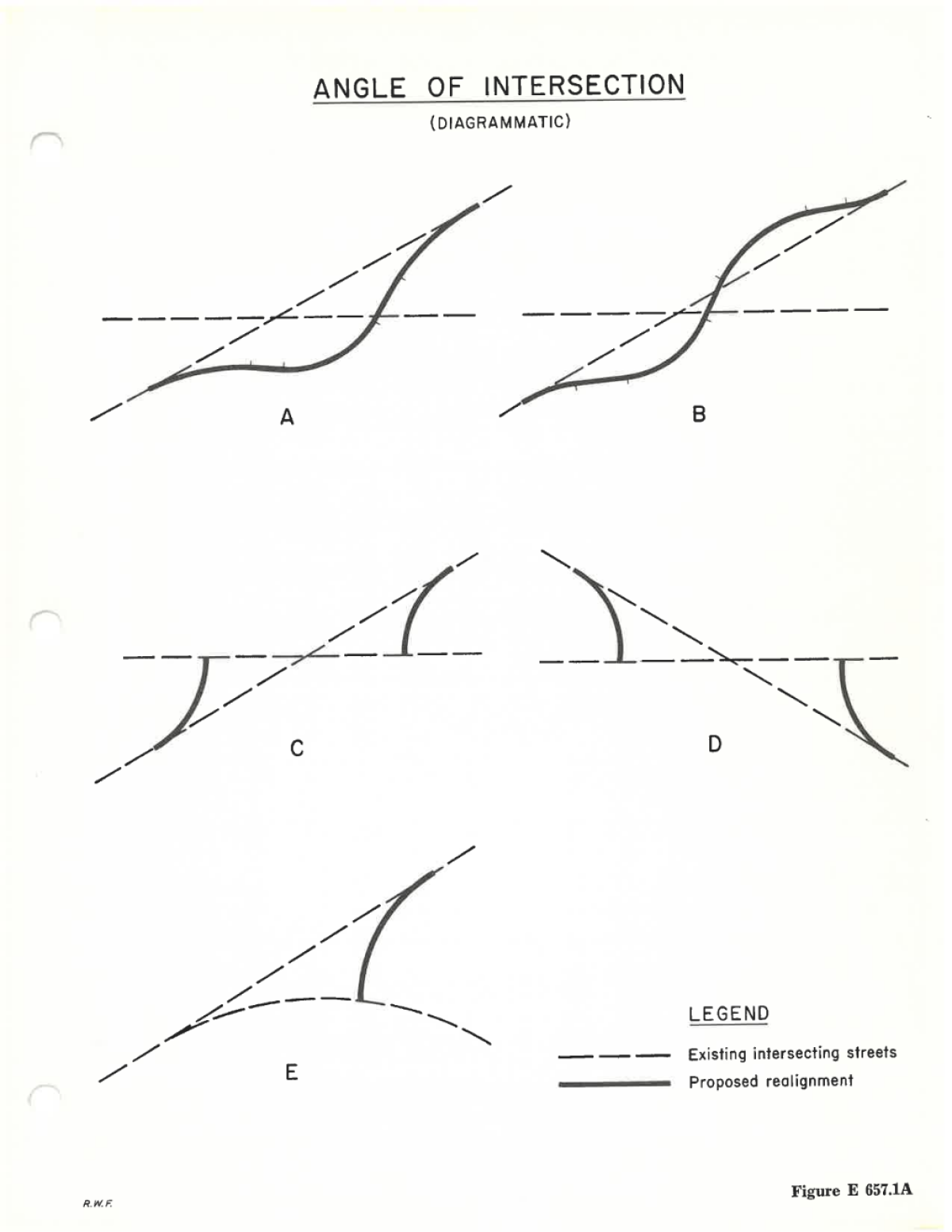

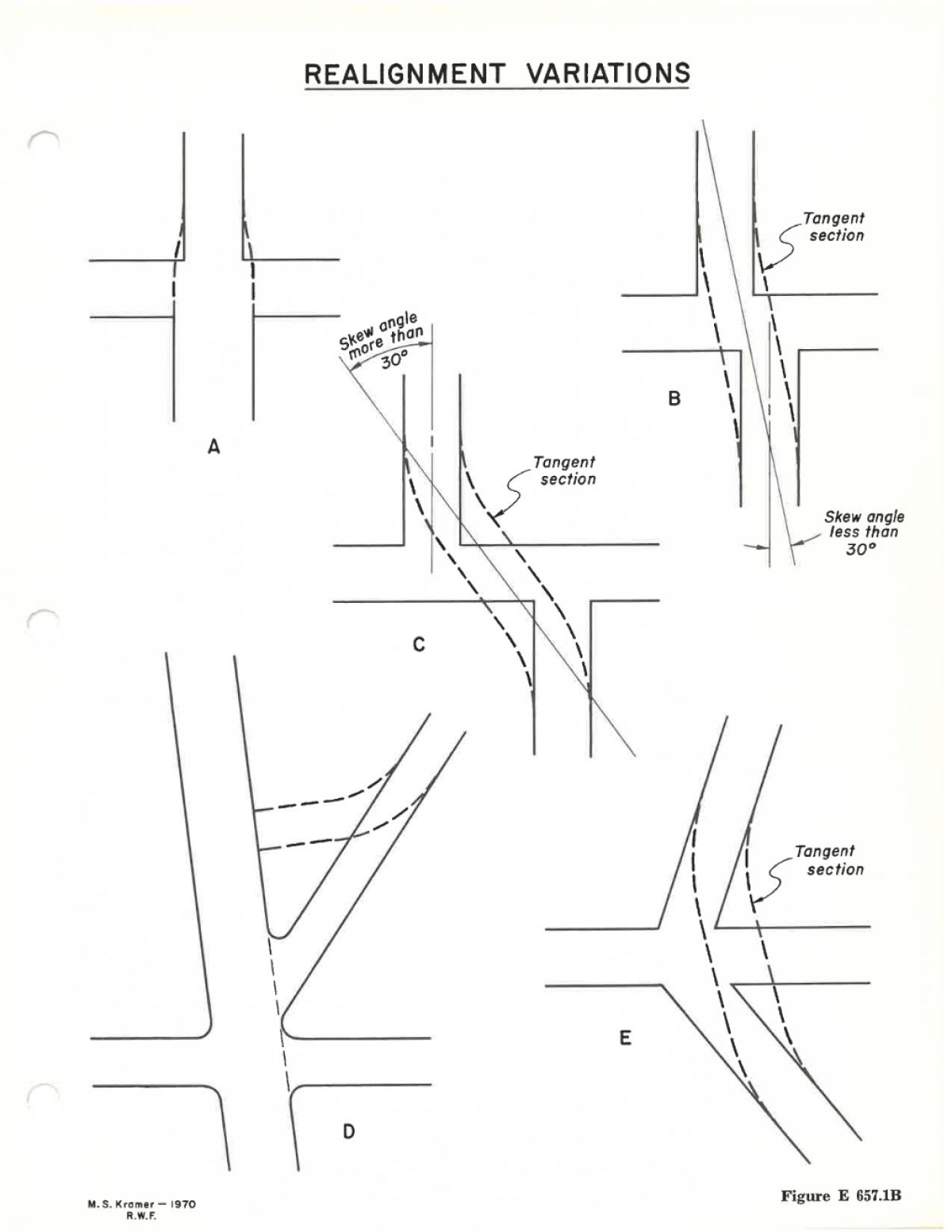

A right-angle intersection provides the most favorable conditions for vehicle operators to judge the relative position and speed of vehicles on the intersecting roadway. In addition, it provides the shortest crossing distance for intersecting traffic streams. Intersecting angles on a skew of not more than 30 degrees do not materially decrease visibility or increase crossing distances. Where the skew angle exceeds 30 degrees, consideration should be given to realignment of the intersecting road as shown in Figures E 657.1A and E 657.1B.

Additional measures that could be taken to reduce (accidents)1 collisions and facilitate traffic movements are shown on Figure E 657.1B and are discussed below:

- Intersection A is an example of an intersection that has a narrow street for one of the legs. The correction indicated is a gradual converging transitional alignment.

- Intersection B is an example of an offset intersection where through traffic must generally slow down considerably or come to a complete stop. The corrective measure indicated is a long- radius reverse curve with intervening tangent sections. The skew angle that is provided should not exceed 30 degrees unless approved by the Division or District Engineer.

- Intersection C is also an example of an offset intersection. The reverse curve alignment as shown creates an intersection angle of more than 30 degrees. If the topography, existing improvements, and economics permit, a large enough radius reverse curve system should be used to provide a skew angle of less than 30 degrees. The corrective measures taken would then be like those in paragraph 2, above.

- Intersection D is an example of a multileg intersection. The extra leg generally creates a large area of vehicular conflict and reduces intersection capacity. Where economically feasible, the corrective measure indicated is to restrict or seal off access to the intersection and realign one leg to form another right-angled "T" intersection. This "T" intersection should be located at a sufficient distance to prevent interference with the main intersection. This realignment then permits the main intersection to be treated as a normal 4-leg intersection Another treatment would be to channelize the intersection. This subject is covered under Subsection E 557.2.

- Intersection E is an example of a sharply angled intersection. The suggested improvement of the alignment is to introduce a large-radius curve to eliminate or reduce the effects of the curb protrusion into the path of an oncoming vehicle. It provides a more logical path for vehicles.

E 557.2 Channelization

At-grade intersections having large, paved areas, such as those with large corner radii and those at oblique angle crossings, permit and encourage uncontrolled vehicle movements, require long pedestrian crossings, and have unused pavement areas. Even at a simple intersection there may be appreciable areas on which some vehicles can wander from the natural and expected paths. Conflicts may be reduced in extent and intensity by including islands in the design layout. An at-grade intersection in which traffic is directed into definite paths by islands is termed a channelized intersection. Channelization is generally included in intersection design for the following purposes:

- Separation of conflicts.

- Control of angles of potential conflict.

- Reduction of excessively large pavement areas.

- Regulation of traffic flow and indication of proper use of an intersection.

- Favoring of the predominant turning movement.

- Protection of pedestrians.

- Protection and storage of turning and crossing vehicles.

- Providing a location for traffic control devices.-

- Discouraging or prohibiting specific movements.

- Control of speed.

E 557.21 Principles of Channelization

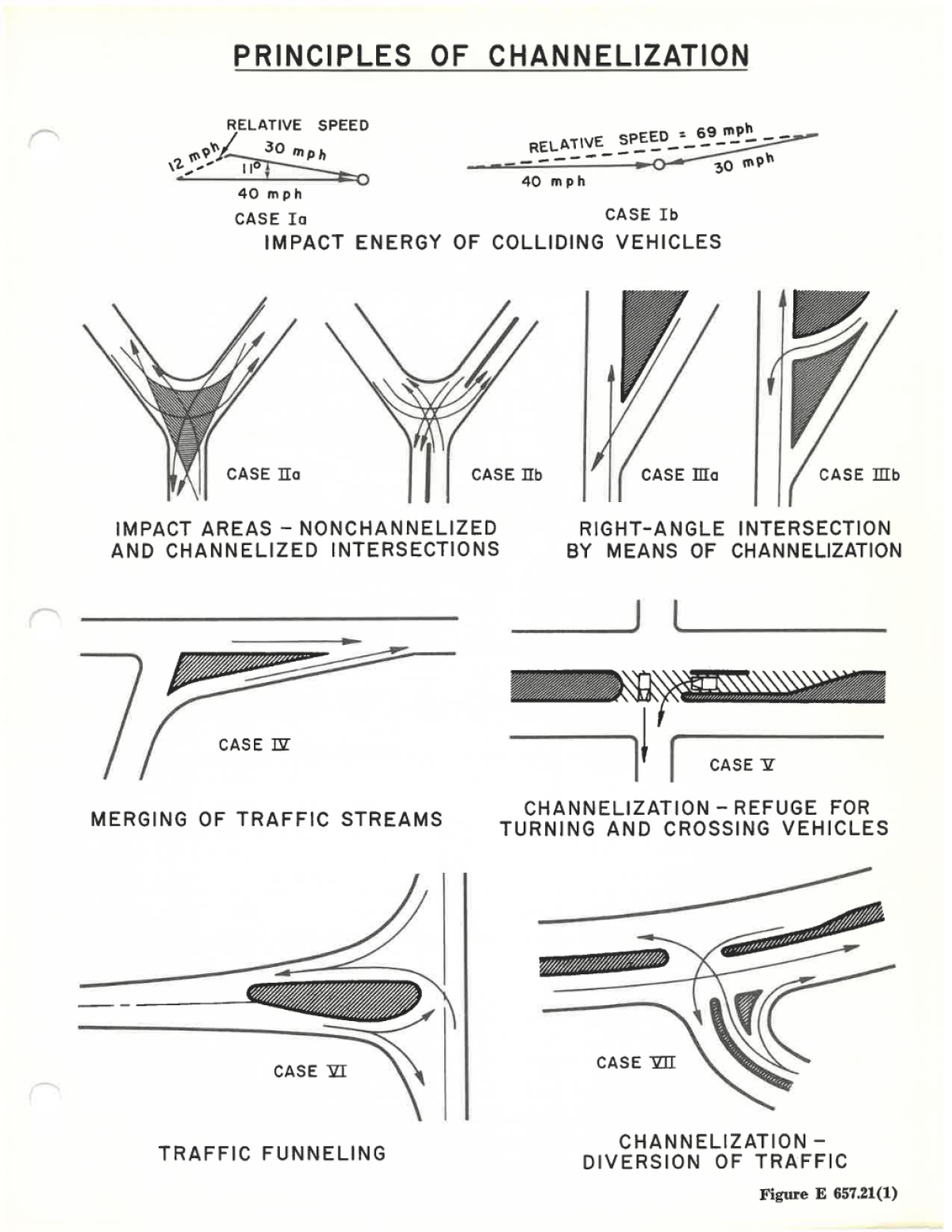

The outline of the principles of channelization that follows is based on the Highway Research Board Special Report No. 74. The titled cases that are shown on Figure E 657.21(1) and illustrate some of the typical channelization patterns that are used for different types of intersections and are discussed below:

- The relative speed and impact energy of intersecting vehicles are functions of vehicle speeds and angle of intersection. The impact energy varies as the square of the speed. The impact energy varies as the square of the speed. The impact energy of colliding vehicles in the diagram of Case Ib is 33 times more than in Case Ia.

- Channelization reduces the area of conflict. Large paved intersectional areas permit less control of vehicle and pedestrian movements. This lack of control may increase (accidents)1 collisions and congestion and reduce operating efficiency of the intersection. The diagram of Case IIa and Case IIb illustrates the differences in impact areas between channelized and non-channelized intersections.

- When traffic streams cross without merging and weaving, the crossing should be made at or near right angles. This angle improves the position for maneuvering or making a change of speed which may be required to avoid conflict. The intersection of traffic streams under this condition tends to:

- Reduce the impact area.

- Reduce the crossing time on the opposing traffic stream.

- Reduce the conflict area size.

- Provide the most favorable angle for drivers to judge the relative position and relative speed of intersecting vehicles.

- Reduce the impact area.

The diagram of Case IIIa illustrates the acute-angled intersection and Case IIIb illustrates the right-angled effect created by channelization.

- Vehicles entering a moving traffic stream at flat angles have a better opportunity to select safe gaps for entering and merging in the stream. Vehicles entering a moving traffic stream at angles greater than 10 degrees to 15 degrees must usually be subjected to stop control. This greater angle reduces the capacity and safety of the intersection because a greater time gap in the moving stream is required for the entrance of a stopped vehicle as compared to the entrance of a moving vehicle. Traffic streams should merge at small angles, as illustrated in the diagram of Case IV.

- Channelization can provide refuge for turning and crossing vehicles of an uncontrolled traffic stream. This may also provide for safer crossing of two or more traffic streams, since the drivers need not select a safe time gap for more than one traffic stream at a time. The shadowed area illustrated in the diagram of Case V provides refuge for a vehicle waiting to cross or enter the traffic stream.

- Funneling subordinates traffic movements to a single lane. It is generally desirable to regulate minor traffic movements to a single lane where they enter a moving traffic stream. The mouth of a separate turning lane should be flared or widened to facilitate easy entrance and then narrowed to a single lane. If properly designed, funneling discourages undesirable overtaking and passing in a conflict area. Funneling must be made readily apparent to the driver. The diagram of Case VI illustrates traffic funneling.

- Islands are used to divert traffic streams to the permitted directions. This discourages drivers from making prohibited turns and going in the wrong direction on one-way streets. The diagram of Case VII illustrates how channelization blocks prohibited turns.

- Channelization is usually required at complex intersections that have many turning movements. The islands also serve as locations for the installation of required traffic control devices. The diagram of Case VII illustrates the use of channelization which provides locations for these traffic control devices.

- Channelization separates and clearly defines points of conflict within the intersection. This allows drivers to be exposed to only one conflict and one decision at a time. The diagram of Case IX illustrates how channelization separates these conflict points.

- Channelization must be provided at signalized intersections with complex turning movements. This permits the sorting of the approaching traffic which may move through the intersection during separate signal intervals. It is also of particular importance when traffic-actuated signal controls are employed. The diagram of Case X illustrates the type of signal control that may be necessary at intersections with these movements.

E 557.22 Channelization Design Considerations

In designing channelization, the following points should be considered in addition to the other factors covered in Section E 550, Intersections At-Grade.

- Be sure channelization is necessary.

- Avoid isolated channelization unless of major proportions.

- Avoid multiple maneuvers, such as merging three movements into one, or one movement offering three or more simultaneous choices.

- Be sure islands are readily visible on approaches.

- Where possible, a few large islands should be used rather than numerous small ones. Raised portions of islands should be offset from the edge of the traveled vehicular paths.

E 557.3 Traffic Islands

These are used to protect vehicles and pedestrians as well as to regulate their movements. They are also used for the location and protection of various types of traffic signs and other traffic devices. Where the prime objective of the traffic island is vehicular guidance and not protection of pedestrians or traffic devices, painted guidelines should be used. Pedestrian islands should be used only on exceptionally wide roadways or in large or irregularly shaped inter- sections where heavy volumes of vehicular traffic make it difficult and dangerous for pedestrians to cross and should be so located as not to create a hazard for motor vehicles.

Traffic islands designated for vehicular control are classified into two separate types:

- Divisional islands, which serve to separate traffic moving in the same or opposite directions. See Section E 660, Medians.

- Channelizing islands, which are designed to confine specific traffic movements in definite channels.

An island may be delineated by paint, raised bars, buttons, curbs, pavement edge, or guideposts.

Vertical curbs should be used for the protection of pedestrians or physical installations and/or traffic islands. Mountable curbs are intended to permit emergency and out-of-control vehicles to cross over or mount the median. Some damage to landscaping is to be expected but should occur infrequently. The type and function of the curb discussed above are also covered in Section E 630, Curbs and Gutters.

Traffic islands should have an absolute minimum area of 50 square feet and a desirable minimum of 75 square feet. The approach end of the island should be designed with an offset to give a desired vehicle path and should be so delineated that it does not surprise the motorist.

It is the City’s practice to provide gutters with a minimum width of 1 foot around islands where possible. However, where water flow is anticipated, 2-foot gutters are provided. See Section E 630, Curbs and Gutters.

E 557.31 Surfacing

The entire raised surface of a curbed traffic island should be paved with PCC. See Subsection E 667.2, Structural Cross-Section. However, consideration should be given to the landscaping of the island. See Subsection E 667.3, Landscaping. Where the landscaped islands are also used as pedestrian refuges in crossing streets, sidewalks should be provided. The sidewalks should be of PCC at least 3 inches thick and at least 4 feet wide.

Some islands are constructed by doweling or extruding curb onto the existing roadway surface. Where the resulting raised island area is 1000 square feet or less, for economic reasons the space between the existing roadway surface and the proposed raised island surface should be poured solid with PCC. In general, where the area of the island is more than 1000 square feet, the raised surface should be paved with PCC 3 inches thick. The subbase required for the roadway surface should also be used under the median surfacing.

In designing the raised island surfacing, cross- sections should be plotted through critical sections. Surface pavement elevations should be designed to ensure surface drainage of storm waters. A minimum grade of 1 percent slope should be provided.

E 557.4 Flared Intersections

An intersection is generally considered flared when the normal or prevailing roadway width is increased by an additional traffic lane at the approaches to the intersection and at one or more of its legs. This provides additional capacity for through and turning movements.

The selection of a particular intersection to be flared is based on relative traffic volumes, turning movements, type of traffic controls anticipated, etc. The type and standards used by the City for the layout of the flared intersection are shown on Figures E 464.2B, Striping Standards for Secondary Highways, Plates I and II, and E 464.2C, Diamond Interchange for Major and Secondary Highways.

Footnotes

- The text in parenthesis is from the legacy Street Design Manual text and has been superseded by the text that follows.

Comments